DNS hijacking allows cybercriminals to modify the DNS records of benign domain names and redirect unsuspecting users to malicious servers. Threat actors compromise domains for various attacks, including men-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks, drive-by downloads, phishing, and scams. DNS hijacking is a pervasive threat that can have catastrophic consequences for domain owners and their users.

An incident on October 22nd, 2016, is a stark example of DNS hijacking. Cybercriminals seized control of the entire online operation of a major Brazilian bank with over 5 million customers and 500 branches worldwide, as reported by Kaspersky Lab.

Threat actors can hijack DNS records using different methods. An attacker can take over the domain owner’s account at a domain registrar or a DNS service provider or infiltrate the registrar/DNS service provider. For example, attackers can use phishing, password guessing or breach another site to take over accounts. In such scenarios, mitigation techniques such as Domain Name System Security Extensions (DNSSEC) or encrypting DNS queries and responses (e.g., DNS over HTTPS and DNS over TLS) are insufficient to prevent attackers from hijacking the records.

Alternatively, attackers can hijack DNS records via DNS cache poisoning or other attacks manipulating DNS responses, such as MitM attacks intercepting communication and modifying the DNS queries on the fly. Cybercriminals hijack DNS records and change the resolution of domains to redirect requests for a domain to a destination they control. DNS hijacking is typically a precursor to other attacks, such as scams or drive-by-downloads.

DNS hijacking is a relatively rare attack that can have a disastrous impact on domain owners, visitors, and customers. Due to its rarity, getting labeled data to train a classifier is hard. Additionally, pDNS data is large, making it challenging to accurately and efficiently find the few DNS hijacking cases.

To address the above problems, we designed a detection pipeline that processes an average of 167 million new DNS records every day. After preprocessing, it extracts 74 features for the remaining candidate DNS hijacking records from over 159 terabytes of passive DNS and geolocation data. We then use a machine learning model to predict whether or not these candidate records are truly the result of DNS hijacking.

Between March and September 2024, our detection pipeline processed over 29 billion new records and identified 6,729 as hijacking, with an average daily detection of 38 records. Recently, we deployed a new version of our model that can detect DNS hijacking in our customers’ traffic in around 10 minutes.

Our detector found several high-profile DNS hijacking cases from the very beginning, including:

- The DNS hijacking of a Hungarian political party’s domain name

- The defacement of a large utility company and large internet service provider (ISP)

- Using the domains of a university and research center to host illicit gambling

Our automatic pipeline found that dkujpest[.]hu, the domain of the Democratic Coalition (DK), was hijacked on June 28th. DK is the largest political opposition to the Hungarian government until recent power shifts. Our detector found the hijacking record just after the attack occurred and two days before some of the most prominent Hungarian news outlets started covering this attack. Our automatic web crawlers found that attackers sent visitors to the below phishing page:

![The webpage of domain dkujpest[.]hu after DNS hijacking.](/assets/img/blog/2024/dns-hijacking-detector/microsoft-phishing.png)

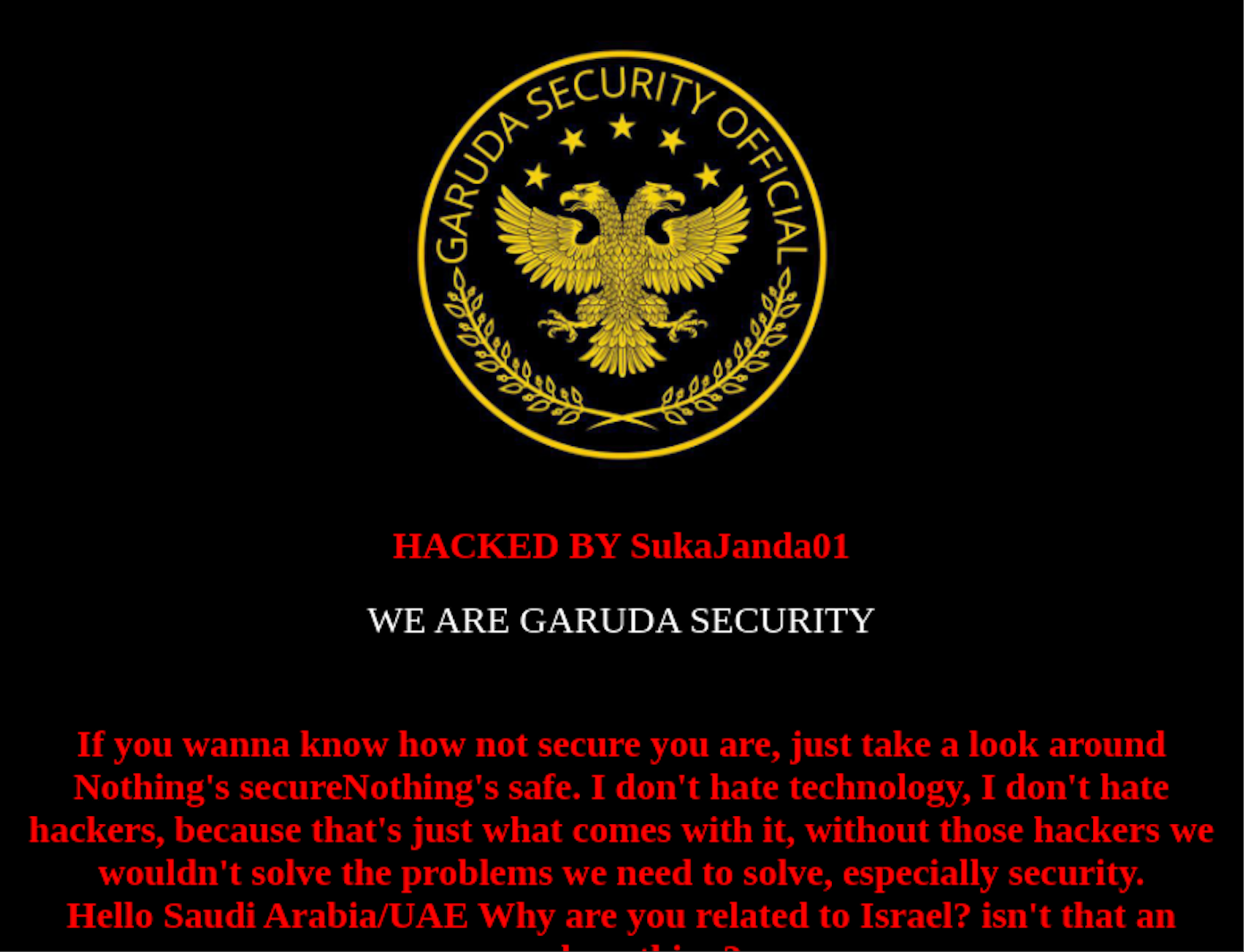

On May 8th, we detected two domains of one of the largest utility management companies in the US, pointing to hijacking IP address 176.9.24[.]28. Garuda hackers defaced the websites of these domains.

On May 25th, we detected a similar DNS hijacking incident by the same threat actors targeting one of the largest ISPs that operates one of the 13 root servers on the Internet, where its A record was hijacked to 176.9.24[.]28.

Our longer Unit42 research blog provides more details on DNS hijacking case studies and our detection process.